Sunday, 14 September 2008

Missing birthdays

Roberta X writes:

In the days when I worked in the movie business (“exhibition†division), one of our company rituals was the monthly lunch to honor any staffers whose birthdays fell during that month. These lunches involved the owner, the office staff (treasurer, film booker, and secretary), the “birthday people,†and any other miscellaneous employees who wanted to show up. The birthday folks got free lunch and drinks,

as well as having their schedule covered so they wouldn’t be required to work for rest of the day. (The importance of this latter point will become evident below. The company also provided a limousine and driver, for similar reasons.[1])

Come Friday noon, all would meet at the company office, to be whisked away to some decent restaurant for lunch and drinks. After lunch, the convivality would advance to a second venue, and possibly a third, shedding along the way anyone who was so unfortunate as to be required to work that evening. The those left would continue as described, with the festivities sometimes lasting until late in the evening; at which point they would often be re-joined by those who had closed up after the night’s last performance.

Now my job was analogous to Roberta’s[2]: I worked in the department that kept the picture on the screen, the sound sounding sweet, the air cool (or warm, as needed), and the lights going on and off as the show required. While there were three others who worked with me, by general agreement anything that lived in the projection booth was my baby.[3] And while Friday afternoon is an excellent time for a drunken an extended lunch (due to the hangover recovery sleeping-in possibilities of the following Saturday morning, Friday afternoon is also the run-up to most theaters’ busiest time of the week, the Friday night/Saturday/Sunday shows. So it was important to have everything functioning as specified by the time the curtains opened on Friday evening, not just because most parts suppliers ran half days (if at all) on Saturday (meaning Stuff Not Repaired by Five o’clock on Friday usually Didn’t Get Fixed until Monday), but also because inferior presentaion presented an irritating (to say the least) prospect for the theater managers and staff.

The core of our group of theaters (encompassing nine screens scattered in ones or twos around a three-county area) were a group of four houses that had originally opened as Jerry Lewis cinemas. These were mini-theaters (an idea quite revolutionary at the time) with one or two auditoriums, each seating about 350 people. The plan, put together in the late sixties by an outfit called Network Cinema Corporation (with Jerry Lewis hired as spokesman/figurehead/name on the marquee), was to sell packaged theatres, fully equipped, to individual investors, who would then operate them as franchisees. Suppposedly, the theaters would only run “family oriented†movies, with bookings and promotion arranged by Network (who would also be the source for concession products and others supplies). The package included some of the first fully automated projection equipment, so projectionists were unnecessary (except in localities where the I.A.T.S.E.’s muscle made such cost-cutting “unwiseâ€). In fact, the setup was such that it only required a couple of people to run the entire operation on “light†nights.

Unfortunately, like so many “deals†where Hollywood-types interact with civilians, the Lewis concept quickly turned into yet another method of extracting cash from suckers. First hitch: Network Cinema lacked the clout to stand up against the existing first-run operators already present in large markets[4] This meant that metro area Lewis theaters couldn’t get newly-released films (even if bidding identical terms, a 600-seat screen outweighs a 300-seat one). Instead they had to make do with second or “sub†runs, and the lower admission prices such programs commanded. Next there was the problem of product: Turned out, there weren’t enough “family-friendly†films being released in the late 60s to give the theaters a continuous stream of such features. And finally, there was often location: The individuals who bought into the Lewis idea usually lacked the capitol (and the real-estate expertise) to get into the major malls. They wound up putting their screens in lower-traffic “neighborhood†centers; where the resulting lower attendance made it impossible to build the kind of track record a theater needs to bid for major pictures.

So, although Network sold packages to people all over the country, the “Lewis†concept succeeded only in small towns without existing theaters (or with existing theaters that had been allowed to become decrepit). Elsewhere, what had been touted as “guaranteed profits†turned out to be hand-to-mouth existence. Disappointed franchisees revolted. Network Cinema vanished in a cloud of litigation, the Jerry Lewis name came off the marquees (to be replaced by generics like “$shopping_center Cinema 1â€), and the theaters that didn’t close right away continued to limp along as before, until the operator gave up his lease or sold out (usually at pennies on the dollar) to a larger group.

There was another aspect which directly relates to my story. When Network Cinema was first getting off the ground, the equipment they put in the projection booth was the same sort of gear that would be installed in any theater. But as more “Lewisâ€-style cinemas were constructed, the suppliers began to develop cheap-n-shoddy stripped-down less expensive substitutes. Altec Lansing built a speaker to replace their more-conventional A7, one that was thinner (required less depth behind the screen, meaning the operator might be able to squeeze one more row of seats into the auditorium), sounded “almost as good,†and was (of course) cheaper. Simplex developed a hard-to-service one-box sound system that replaced the previously separate amplifier, pre-amplifier, and exciter-lamp power supply. And an outfit called Optical Radiation Corporation dreamed up an all-in-one xenon projection lamp and power supply. Of the screens in our chain, six of them were outfitted with this “discount price†equipment when we acquired them.

The Optical Radiation Lamps were real pieces of work.[5] Oh, it was a good idea, provided “good†is defined as “let’s squeeze a 1000-watt xenon-arc lamp and its power supply into a box the size of a small suitcase!†The result was a jam-packed collection of parts: Capacitors, circuit boards, transformers plus the lamp itself and its associated reflector, all very tightly packed. A pair of 5˜ muffin fans, in hope of keeping the thing cool enough that it wouldn’t destroy itself. All wrapped up in a four-piece housing (two end castings and an upper and lower shroud) that tended to fall apart when you opened it, which made it a pain to service. The power supply was a tiny, electronically regulated thing, which got flakey if too warm, causing the lamp brightness to fluctuate. Connections would loosen and overheat. The lamps themselves would occasionally explode. But hey, at least you didn’t have to put in a new set of carbons every reel!

And one more thing. Because of the theaters’ cheap construction (as in “no separate air conditioner for the projection boothâ€), the booth’s exhaust fans would draw in air from the lobby. Where there was a popcorn popper. Popping lots of popcorn. Each batch releasing a cloud of steam flavored with popcorn oil drops. Which got sucked into the projection booth. Where it then condensed onto anything, especially anything that that might have a fan pulling lots of air through it, like... can you say... “projection lamps?†Yep, everything inside those lamphouses wound up plated with a film of popcorn oil. (Ewwww! First step after opening them up was to grab a roll of paper towels and wipe everything off.)

booth’s exhaust fans would draw in air from the lobby. Where there was a popcorn popper. Popping lots of popcorn. Each batch releasing a cloud of steam flavored with popcorn oil drops. Which got sucked into the projection booth. Where it then condensed onto anything, especially anything that that might have a fan pulling lots of air through it, like... can you say... “projection lamps?†Yep, everything inside those lamphouses wound up plated with a film of popcorn oil. (Ewwww! First step after opening them up was to grab a roll of paper towels and wipe everything off.)

You might get the impression that the ORCs (as we “affectionately†called them) were unreliable. You’d be right. They were a constant problem, and as soon as funds were available we replaced the lot of them (along with the cheap speakers and those underpowered one-box sound systems). But until that day, we (mostly meaning “Iâ€) had to keep stuff operating. Which gets us to the “I told you that story so I can finish telling you this one†point of my narrative.

Of the seven screens in our four “Lewis†theaters, six of them had ORCs, giving us a total of twelve of the things.[6] I never calculated the mean time between failure, but early on it seemed like we were always working on them. Once we had caught up on the previous operators’ deferred (“put it off until something breaksâ€) maintenance, things got a bit better, but it was the rare month that went by without at least one ORC giving us problems. Usually toward the end of the week. And more often than not, “birthday Friday†would find me stuck in a projection booth somewhere, trying to bring one of those balky ORCs back to life.

Except for October. The month containing my birthday. In October, it was inescapable: For my first four years with the company, I missed my birthday lunch. Because of one of thoser #$(@*&%^! ORCs. Because the show must go on.

Howzzat for dedication?

(And I see that Roberta lost her Saturday to “technical difficulties†this week.)

(Author’s note: While I was poking around the web in search of the links included above, I found this collection of photos taken at the Fortuna Theatre in Fortuna California. Movie gadgetry geeks will enjoy.)

Elsewhere:

-----

Comments are disabled.

Post is locked.

(With this entry, O.G. introduces the “Geezering†department, featuring Tall Tales of the Distant Past, All be Mostly True (with only Occasional Slight Enhancement for Literary Effect). Exact dates, places, and dramatis personae may be subject to Lapses Of Memory, and Some Identities may be Obscured in order to Protect the Guilty.)

Roberta X writes:

“Can you hear the reason I did things like miss a friend’s birthday?â€Yep, been there, done that.

In the days when I worked in the movie business (“exhibition†division), one of our company rituals was the monthly lunch to honor any staffers whose birthdays fell during that month. These lunches involved the owner, the office staff (treasurer, film booker, and secretary), the “birthday people,†and any other miscellaneous employees who wanted to show up. The birthday folks got free lunch and drinks,

as well as having their schedule covered so they wouldn’t be required to work for rest of the day. (The importance of this latter point will become evident below. The company also provided a limousine and driver, for similar reasons.[1])

Come Friday noon, all would meet at the company office, to be whisked away to some decent restaurant for lunch and drinks. After lunch, the convivality would advance to a second venue, and possibly a third, shedding along the way anyone who was so unfortunate as to be required to work that evening. The those left would continue as described, with the festivities sometimes lasting until late in the evening; at which point they would often be re-joined by those who had closed up after the night’s last performance.

o-o-0-o-o

Now my job was analogous to Roberta’s[2]: I worked in the department that kept the picture on the screen, the sound sounding sweet, the air cool (or warm, as needed), and the lights going on and off as the show required. While there were three others who worked with me, by general agreement anything that lived in the projection booth was my baby.[3] And while Friday afternoon is an excellent time for a drunken an extended lunch (due to the hangover recovery sleeping-in possibilities of the following Saturday morning, Friday afternoon is also the run-up to most theaters’ busiest time of the week, the Friday night/Saturday/Sunday shows. So it was important to have everything functioning as specified by the time the curtains opened on Friday evening, not just because most parts suppliers ran half days (if at all) on Saturday (meaning Stuff Not Repaired by Five o’clock on Friday usually Didn’t Get Fixed until Monday), but also because inferior presentaion presented an irritating (to say the least) prospect for the theater managers and staff.

o-o-0-o-o

The core of our group of theaters (encompassing nine screens scattered in ones or twos around a three-county area) were a group of four houses that had originally opened as Jerry Lewis cinemas. These were mini-theaters (an idea quite revolutionary at the time) with one or two auditoriums, each seating about 350 people. The plan, put together in the late sixties by an outfit called Network Cinema Corporation (with Jerry Lewis hired as spokesman/figurehead/name on the marquee), was to sell packaged theatres, fully equipped, to individual investors, who would then operate them as franchisees. Suppposedly, the theaters would only run “family oriented†movies, with bookings and promotion arranged by Network (who would also be the source for concession products and others supplies). The package included some of the first fully automated projection equipment, so projectionists were unnecessary (except in localities where the I.A.T.S.E.’s muscle made such cost-cutting “unwiseâ€). In fact, the setup was such that it only required a couple of people to run the entire operation on “light†nights.

Unfortunately, like so many “deals†where Hollywood-types interact with civilians, the Lewis concept quickly turned into yet another method of extracting cash from suckers. First hitch: Network Cinema lacked the clout to stand up against the existing first-run operators already present in large markets[4] This meant that metro area Lewis theaters couldn’t get newly-released films (even if bidding identical terms, a 600-seat screen outweighs a 300-seat one). Instead they had to make do with second or “sub†runs, and the lower admission prices such programs commanded. Next there was the problem of product: Turned out, there weren’t enough “family-friendly†films being released in the late 60s to give the theaters a continuous stream of such features. And finally, there was often location: The individuals who bought into the Lewis idea usually lacked the capitol (and the real-estate expertise) to get into the major malls. They wound up putting their screens in lower-traffic “neighborhood†centers; where the resulting lower attendance made it impossible to build the kind of track record a theater needs to bid for major pictures.

So, although Network sold packages to people all over the country, the “Lewis†concept succeeded only in small towns without existing theaters (or with existing theaters that had been allowed to become decrepit). Elsewhere, what had been touted as “guaranteed profits†turned out to be hand-to-mouth existence. Disappointed franchisees revolted. Network Cinema vanished in a cloud of litigation, the Jerry Lewis name came off the marquees (to be replaced by generics like “$shopping_center Cinema 1â€), and the theaters that didn’t close right away continued to limp along as before, until the operator gave up his lease or sold out (usually at pennies on the dollar) to a larger group.

There was another aspect which directly relates to my story. When Network Cinema was first getting off the ground, the equipment they put in the projection booth was the same sort of gear that would be installed in any theater. But as more “Lewisâ€-style cinemas were constructed, the suppliers began to develop cheap-n-shoddy stripped-down less expensive substitutes. Altec Lansing built a speaker to replace their more-conventional A7, one that was thinner (required less depth behind the screen, meaning the operator might be able to squeeze one more row of seats into the auditorium), sounded “almost as good,†and was (of course) cheaper. Simplex developed a hard-to-service one-box sound system that replaced the previously separate amplifier, pre-amplifier, and exciter-lamp power supply. And an outfit called Optical Radiation Corporation dreamed up an all-in-one xenon projection lamp and power supply. Of the screens in our chain, six of them were outfitted with this “discount price†equipment when we acquired them.

The Optical Radiation Lamps were real pieces of work.[5] Oh, it was a good idea, provided “good†is defined as “let’s squeeze a 1000-watt xenon-arc lamp and its power supply into a box the size of a small suitcase!†The result was a jam-packed collection of parts: Capacitors, circuit boards, transformers plus the lamp itself and its associated reflector, all very tightly packed. A pair of 5˜ muffin fans, in hope of keeping the thing cool enough that it wouldn’t destroy itself. All wrapped up in a four-piece housing (two end castings and an upper and lower shroud) that tended to fall apart when you opened it, which made it a pain to service. The power supply was a tiny, electronically regulated thing, which got flakey if too warm, causing the lamp brightness to fluctuate. Connections would loosen and overheat. The lamps themselves would occasionally explode. But hey, at least you didn’t have to put in a new set of carbons every reel!

And one more thing. Because of the theaters’ cheap construction (as in “no separate air conditioner for the projection boothâ€), the

booth’s exhaust fans would draw in air from the lobby. Where there was a popcorn popper. Popping lots of popcorn. Each batch releasing a cloud of steam flavored with popcorn oil drops. Which got sucked into the projection booth. Where it then condensed onto anything, especially anything that that might have a fan pulling lots of air through it, like... can you say... “projection lamps?†Yep, everything inside those lamphouses wound up plated with a film of popcorn oil. (Ewwww! First step after opening them up was to grab a roll of paper towels and wipe everything off.)

booth’s exhaust fans would draw in air from the lobby. Where there was a popcorn popper. Popping lots of popcorn. Each batch releasing a cloud of steam flavored with popcorn oil drops. Which got sucked into the projection booth. Where it then condensed onto anything, especially anything that that might have a fan pulling lots of air through it, like... can you say... “projection lamps?†Yep, everything inside those lamphouses wound up plated with a film of popcorn oil. (Ewwww! First step after opening them up was to grab a roll of paper towels and wipe everything off.)You might get the impression that the ORCs (as we “affectionately†called them) were unreliable. You’d be right. They were a constant problem, and as soon as funds were available we replaced the lot of them (along with the cheap speakers and those underpowered one-box sound systems). But until that day, we (mostly meaning “Iâ€) had to keep stuff operating. Which gets us to the “I told you that story so I can finish telling you this one†point of my narrative.

o-o-0-o-o

Of the seven screens in our four “Lewis†theaters, six of them had ORCs, giving us a total of twelve of the things.[6] I never calculated the mean time between failure, but early on it seemed like we were always working on them. Once we had caught up on the previous operators’ deferred (“put it off until something breaksâ€) maintenance, things got a bit better, but it was the rare month that went by without at least one ORC giving us problems. Usually toward the end of the week. And more often than not, “birthday Friday†would find me stuck in a projection booth somewhere, trying to bring one of those balky ORCs back to life.

Except for October. The month containing my birthday. In October, it was inescapable: For my first four years with the company, I missed my birthday lunch. Because of one of thoser #$(@*&%^! ORCs. Because the show must go on.

Howzzat for dedication?

(And I see that Roberta lost her Saturday to “technical difficulties†this week.)

(Author’s note: While I was poking around the web in search of the links included above, I found this collection of photos taken at the Fortuna Theatre in Fortuna California. Movie gadgetry geeks will enjoy.)

Elsewhere:

Shermlock:

More:

Earlier this year on my birthday I went to work to find three of the four drives in the RAID array of our web server had failed. Ouch.

More:

I had to kill some rabbits for a medical experiment a while back. Ugh. Said experiment is why I am now an electrical engineer - all I kill is capacitors, and those are fun to blow up.

Come to think of it, blowing up rabbits is probably fun (â€One, two, five!â€). I, on the other hand, had to watch their hearts slow to a stop as the anesthetic took effect and then cut their legs off and carve all the meat off the bone. Then I had to use a hacksaw to cut off the portion of the bone we were testing, and then I had to ride my bicycle across campus with a bag of rabbit bones in my backpack. On my birthday. - Mrs. Peel

-----

[1] This was also the company that maintained an office tapper, employees and guests, for the use of. Different world...

[2] but, I get the impression, my job was far more grunt-n-groan and smashed-fingers than hers. Ask me about the time four of us hauled an air conditioning compressor (approximately the size and weight of a 327 V-8) up the side of a two-story building using main strength and awkwardness, or the Sunday morning I spent inside of a marquee rewiring the neon.

[3] “What, you afraid of those high-pressure lamps? Just because they explode every so often when you’re changing them...†(And though we didn’t have anything approaching the stardrive’s 36kV voltages, I can state from experience that a 900-volt plate supply tingles plenty ’nough when its rectifier filament winding decides to short to chassis, and you grab the power switch.)

[4] Also at the time, the studios were still operating under restrictions imposed in the 1940-48 antitrust cases, which (supposedly) limited their ability to make booking deals that would block-book groups of theaters. This they used as an excuse for not dealing with Network.

[5] I went Googling for a reference/image and failed to find one. Perhaps no one wants to have anything to do with them. (Not surprising!) Although if you poke around, you can (30 years later!) still find them in use in some theaters! (Hi, Susie! When you gonna come to the blogmeet!)

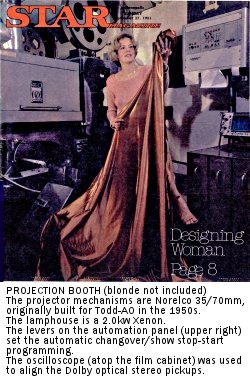

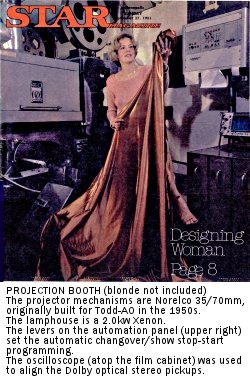

[6] Two projectors/lamphouses per screen. Most theaters today use a “platter†system for handling film: The entire show is loaded onto one enormous reel, which then runs through a single mechanism. (Convenient, unless the film breaks!) Our screens used a transitional system: A pair of projectors using “program reels,†each of which held between sixty and eighty minutes worth of film (that’s 3-4 “exchange†reels, the way the print is shipped). A piece of foil near the end of the reel would trigger a sensor which initiated the (hopefully, undetectable) changeover between machines. The manager would then rewind/rethread at his convenience. The advantages were that in case of failure you could always limp along on one machine (with interruptions every hour or so) if you had to, or, if a print showed up late, you could actually run the show directly from the exchange reels, with projector switches every twenty minutes (not an agreeable prospect, but better than cancelling the 7 p.m. Friday show because you’re still winding film off). The disadvantage: Twice as much Evil Equipment, waiting to break down.

[2] but, I get the impression, my job was far more grunt-n-groan and smashed-fingers than hers. Ask me about the time four of us hauled an air conditioning compressor (approximately the size and weight of a 327 V-8) up the side of a two-story building using main strength and awkwardness, or the Sunday morning I spent inside of a marquee rewiring the neon.

[3] “What, you afraid of those high-pressure lamps? Just because they explode every so often when you’re changing them...†(And though we didn’t have anything approaching the stardrive’s 36kV voltages, I can state from experience that a 900-volt plate supply tingles plenty ’nough when its rectifier filament winding decides to short to chassis, and you grab the power switch.)

[4] Also at the time, the studios were still operating under restrictions imposed in the 1940-48 antitrust cases, which (supposedly) limited their ability to make booking deals that would block-book groups of theaters. This they used as an excuse for not dealing with Network.

[5] I went Googling for a reference/image and failed to find one. Perhaps no one wants to have anything to do with them. (Not surprising!) Although if you poke around, you can (30 years later!) still find them in use in some theaters! (Hi, Susie! When you gonna come to the blogmeet!)

[6] Two projectors/lamphouses per screen. Most theaters today use a “platter†system for handling film: The entire show is loaded onto one enormous reel, which then runs through a single mechanism. (Convenient, unless the film breaks!) Our screens used a transitional system: A pair of projectors using “program reels,†each of which held between sixty and eighty minutes worth of film (that’s 3-4 “exchange†reels, the way the print is shipped). A piece of foil near the end of the reel would trigger a sensor which initiated the (hopefully, undetectable) changeover between machines. The manager would then rewind/rethread at his convenience. The advantages were that in case of failure you could always limp along on one machine (with interruptions every hour or so) if you had to, or, if a print showed up late, you could actually run the show directly from the exchange reels, with projector switches every twenty minutes (not an agreeable prospect, but better than cancelling the 7 p.m. Friday show because you’re still winding film off). The disadvantage: Twice as much Evil Equipment, waiting to break down.

Posted by: Old Grouch in

Geezering

at

02:29:49 GMT

| No Comments

| Add Comment

Post contains 2197 words, total size 20 kb.

79kb generated in CPU 0.0094, elapsed 0.0549 seconds.

50 queries taking 0.0479 seconds, 108 records returned.

Powered by Minx 1.1.6c-pink.

50 queries taking 0.0479 seconds, 108 records returned.

Powered by Minx 1.1.6c-pink.